PITTSBURGH (AP) — The legends of pastoral fields. The detailed history and meticulous attention to continuity. The sight of kids playing ball. The hush that descends when you walk into the Hall of Fame. Each implicitly casts the universe of baseball as a magical land that touches, but maybe isn’t precisely part of, the “real” world in which we live. “The whole history of baseball,” the writer Bernard Malamud once said, “has the quality of mythology.”

Since the game’s early days, that mythology has been constructed — often deliberately — to set itself apart. But sometimes things happen that demonstrate otherwise, and reality pokes through.

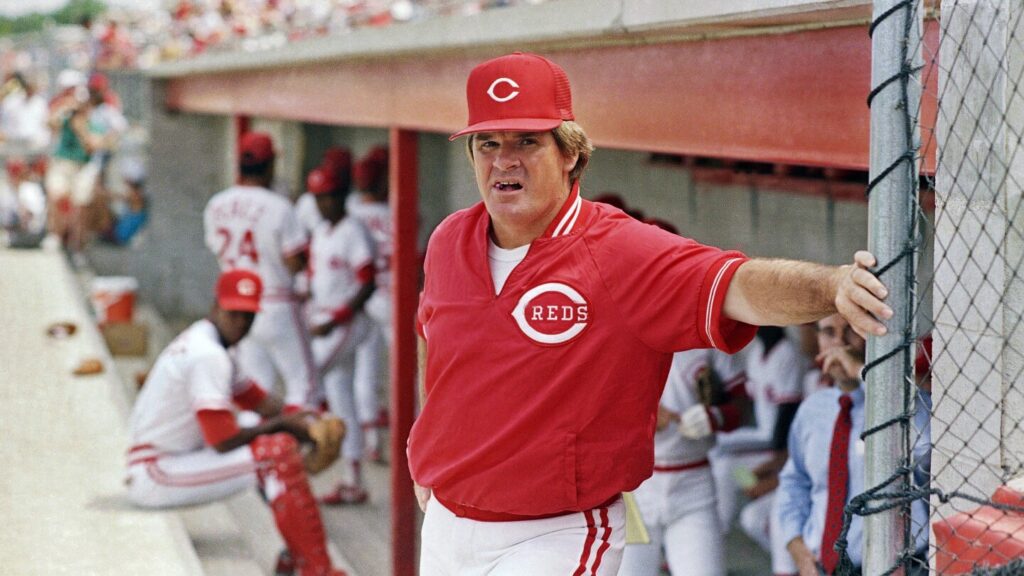

One of those things unfolded this week when Commissioner Rob Manfred decided that permanent bans from baseball expire upon the death of the banned player. In a single moment, he changed the possible posthumous career trajectory of two preposterously talented ballplayers — Pete Rose and “Shoeless Joe” Jackson, one banned for decades for gambling on baseball, the other for more than a century for abetting gamblers. Each is now eligible for the Hall of Fame.

Some welcomed it. “A great day for baseball,” said Rose’s Philadelphia Phillies teammate, Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt. Others chose the online equivalent of spitting disgustedly on the ground. “A very dark day for baseball,” said Marcus Giamatti, son of the late baseball commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti, who banned Rose in 1989. On social media, many wondered whether Manfred had responded to President Donald Trump’s stated desire that Rose be reinstated.

The reality, though, is this: No matter what you think of Manfred’s decision, baseball and the larger world around it collide far more often than the purists might wish — and have since the game’s early decades.

The real world infused the game from its origins

A national pastime can hardly avoid reflecting the values of the culture it serves. That means two things.

— First, American society is built on stories. Where other civilizations have hundreds or thousands of years of common culture behind their nationhood, Americans willed their republic into existence on stories like the “shining city upon a hill,” “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” “all men are created equal.” Then they built it out with tales of the frontier and erected industrial story factories like Hollywood and Madison Avenue. Isn’t it natural, then, that the game many think helped define America would be built on some tall tales, too?

— But second, this is a land of messy politics and jockeying for power and money and — let’s face it — the silencing of less powerful groups. Who could expect a national pastime, however mythic its public-facing ambitions, not to interact with — and be affected by — the society in which it operates?

That meant sharp-elbowed business machinations in the late 19th century that saw the rise and fall of an entirely new league in the course of a single season — and player-contract actions in its wake that led to criticism of the Pittsburgh Alleghenies as “piratical,” inspiring a team nickname that has endured to this day.

It meant the mob-backed, gambling-fueled “throwing” of the 1919 World Series by several Chicago White Sox players — a group henceforth known as the “Black Sox” — that led to the appointment of the first baseball commissioner, a man with the unlikely name of Kenesaw Mountain Landis. He almost immediately banned those accused of involvement from the game, including “Shoeless Joe,” who was remythologized in the 1989 film “Field of Dreams.” As of this week, Jackson has been reinstated — 74 years after his death.

It meant a game that reflected the racism of the nation around it, which kept Black men out until Jackie Robinson famously broke the color barrier in 1947. And it meant a policy on free agency that stacked the deck in favor of owners until a center fielder named Curt Flood, another Black man, took exception to it and took action, sending his name echoing across courtrooms and even Congress after saying: “I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold.”

It meant no less than nine lockouts or strikes over the past six decades — underscoring that baseball, like many other American institutions, is not insulated from labor unrest. It meant cocaine scandals and PED scandals and sign-stealing scandals. Reckoning a century-plus of anxiety about the game’s integrity with a suddenly betting-obsessed sports landscape foisted on baseball by a Supreme Court ruling. Arguments in zoning hearing boards, planning commissions, economic development conferences and city councils over new stadiums, bond issues, local referendums and attempts to figure out precisely where baseball teams fit into their communities.

Politics even figured in attempts during the early 20th century to figure out where baseball came from.

The Mills Commission, assembled in 1905 to suss out the game’s origins, found itself confronted with two competing narratives: In one, put forth by baseball pioneer Henry Chadwick, the game evolved from something English. In the other — a convenient American narrative if there ever was one — a man named Abner Doubleday laid out a diamond in 1839 on a cow pasture in upstate New York, and baseball was born.

The bucolic Doubleday narrative, endorsed by the commission and by baseball itself, flourished for decades. It was debunked long ago in favor of more diffuse origins, which is how history usually actually unfolds.

But the legend’s power pushed it into the national conversation to the point that the place where Doubleday purportedly invented the game became not only the home to the Hall of Fame but a metaphor for greatness, baseball and otherwise: Cooperstown.

Baseball’s endurance relies upon its myths

None of this should surprise us. Ultimately, baseball is a lively collage of American life — a game, a business, a political arena, a form of professional entertainment. It has been a repository of a rising nation’s big dreams, of children’s hero worship, of teenagers’ ambitions and old men’s laments.

“Baseball is play, not work — even when played by professionals, for whom it is indeed work — and so stands aside from the normal conduct of everyday life: business, economy, government,” John Thorn, Major League Baseball’s official historian, said Wednesday.

It certainly tries. On Wednesday night, Cincinnati — the team with which Rose is most associated in a city where his mythology never flagged — honored him. People posed in front of a statue of him. The word “legend” was tossed around. In a twist worthy of a “Twilight Zone” episode, Rose’s old team happened to be playing the Chicago White Sox — Jackson’s old team.

Many fans go to ballparks to escape the world. My late father, a Cleveland fan born in 1922 three years after the Black Sox scandal, used to say in his older years that the Indians’ old stomping ground, League Park, where he used to go as a boy, was “a refuge from the things I worried about.”

At every pro baseball game, all of the calibrated trappings make one thing easy to conclude: The game thinks of itself as pure and wants others to think that too. Sometimes, though, the magic is in the blemishes. Each time the real world intrudes on baseball, many argue that the game emerges stronger — even as it struggles to stay relevant in a 21st-century marketplace of sports and entertainment.

And as it grows harder and harder for baseball — for anything, really — to be insulated from the reality of the world, myths have a tougher time taking hold. In that vein, we’ll leave the final words to Pete Rose himself, from an interview in 2014 — a rejection of mythology from a ballplayer long enveloped in myth.

“When guys do books or stories,” he said, “all I like to see is the truth.”

___

Ted Anthony, director of new storytelling and newsroom innovation for The Associated Press, has written about American culture since 1990.

___

AP MLB: https://apnews.com/hub/MLB

Read the full article here