Like a lot of Democrats these days, Chris Murphy has been doing some soul searching. For years, the Connecticut Senator, who took office shortly after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, was one of the nation’s most outspoken advocates for tighter gun laws. Gun safety was so important, he argued, that supporting an assault-weapons ban should be mandatory for Democratic leaders.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Recently, Murphy has come to believe he was wrong. Not about tougher gun laws, but about trying to force all Democrats to adopt his position. “I bear some responsibility for where we are today,” he told me in a phone interview in April. “I spent a long time trying to make the issue of guns a litmus test for the Democratic Party. I think that all of the interest groups that ended up trying to apply a litmus test for their issue ended up making our coalition a lot smaller.”

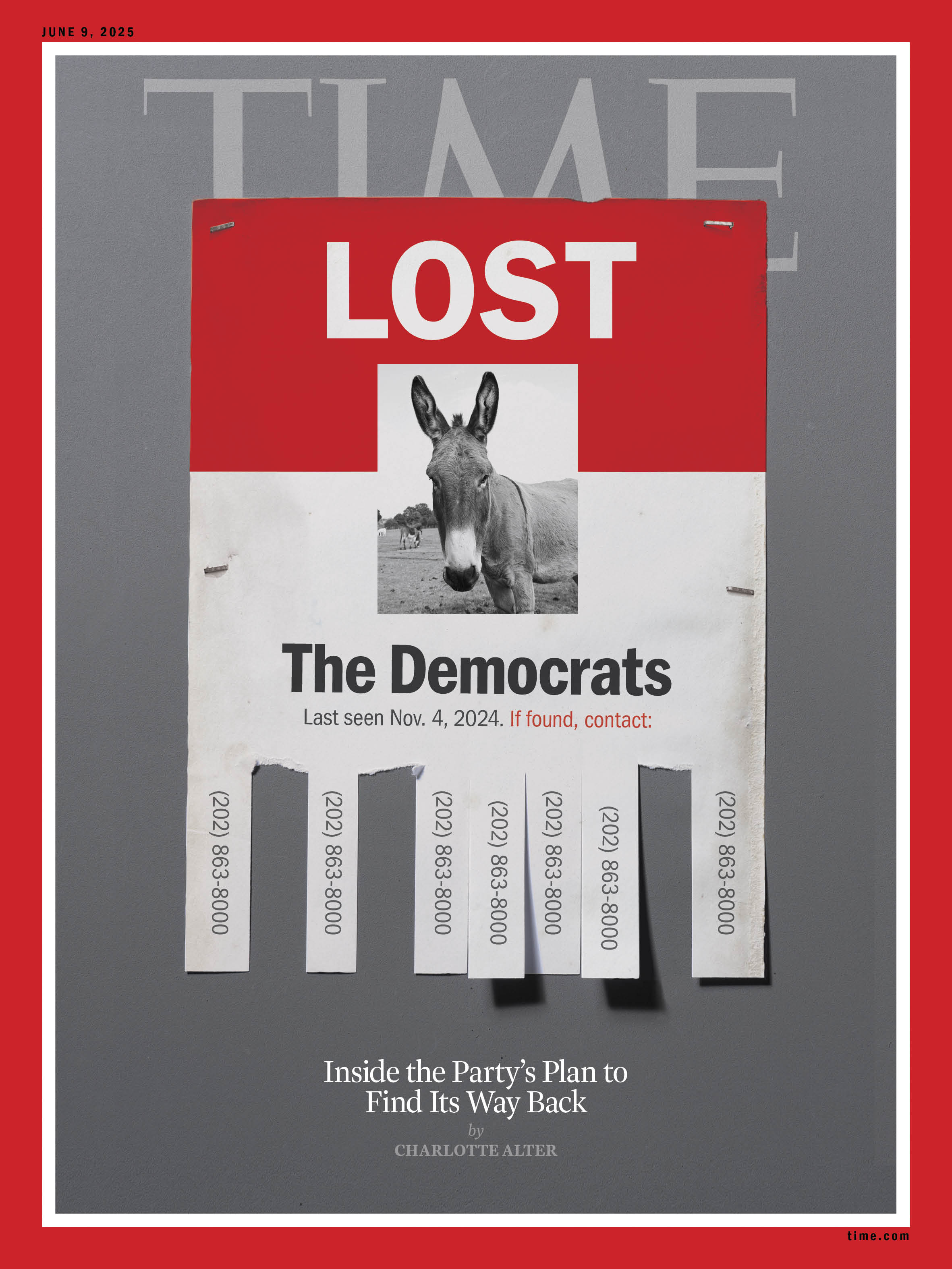

Murphy’s shift in thinking is part of the reckoning that has gripped the party since President Donald Trump’s victory in November. Democrats could dismiss Trump’s first win as a fluke. His second, they know, was the product of catastrophic failure—a nationwide rejection of Democratic policies, Democratic messaging, and the Democrats themselves. The party got skunked in every battleground state and lost the popular vote for the first time in 20 years. They lost the House and the Senate. Their support sagged with almost every demographic cohort except Black women and college-educated voters. Only 35% of Democrats are optimistic about the future of the party, according to a May 14 AP poll, down from nearly 6 in 10 last July. Democrats have no mojo, no power, and no unifying leader to look to for a fresh start.

Everyone knows how bad things are. “As weak as I’ve ever seen it,” says Representative Jared Golden of Maine, who represents a district Trump won. Trump’s second term is “worse than everyone imagined,” says Nevada Senator Jacky Rosen. The Democratic National Committee has offered few answers as it prepares to release a “postelection review” sometime this summer. “I don’t like to call it an ‘autopsy’ because our party’s not dead—we’re still alive and kicking,” explains Ken Martin, the new party chair. “Maybe barely, but we are.”

You already know most of the reasons for the 2024 fiasco. Joe Biden was too old to be President, and just about everybody but Joe Biden knew it. His sheer oldness undermined all efforts to sell his policies effectively. Democrats lost touch with the working class, with men, with voters of color, with the young. Voters saw Democrats as henpecked by college-campus progressives, overly focused on “woke” issues like diversity and trans rights. They tried to convince people that the economy was good when it didn’t feel good; they tried to convince people that inflation and illegal immigration were imaginary problems. In an era when voters around the globe were in an anti-incumbent mood, Democrats were stuck defending the status quo. The pandemic election of 2020 and the post-Dobbs midterms in 2022 lulled top party officials into a dangerous complacency. They thought Americans hated Trump enough to accept an unsatisfying alternative. They thought wrong.

Over the past two months, I’ve spoken to dozens of prominent Democrats, from Senators to strategists, frontline House members to upstart progressives, and activists to top DNC officials, in an effort to figure out how the party can chart its way back. I asked them all versions of the same questions. How did they dig this hole, and how can they get out of it? What ideas do Democrats stand for, beyond opposing an unpopular President? How can they reconnect with the voters they’ve lost? Who should be leading them, and what should they be saying? In other words: What’s the plan?

Many of these conversations made my head hurt. Democrats kept presenting cliches as insights and old ideas as new ideas. Everybody said the same things; nobody seemed to be really saying anything at all. But in between feeble platitudes about “showing up and listening” and “fighting for the working class” and “meeting people where they are,” a few common threads emerged.

Democrats know they have a branding problem that transcends policy, messaging, or leadership questions. They largely agree they need to re-center economic issues in their messaging and develop what some are calling a “patriotic populism” to counter Trump. They need to build a bigger tent. Many moderate Democrats want to sideline the activist groups that pressured elected officials to take unpopular positions. Even many progressives are retreating from the purity politics that reigned in the Trump era. They know they need fresh ideas and new leaders, even though they can’t always agree on how to find them.

The intraparty squabbles between moderates and progressives that have dominated the past decade have given way to different fault lines. “If you’re talking about ‘conservative’ or ‘liberal,’ or ‘progressive’ or ‘moderate,’ you’re missing the whole f-cking point,” says Representative Pat Ryan, who outran Kamala Harris by double digits in his purple district in New York’s Hudson Valley. “It’s not progressive or moderate. It’s status quo or change. It’s for the people or for the elites.”

After a brutal winter, Democrats are beginning to show signs of life. The party won a crucial supreme court race in Wisconsin and picked up two seats in the Pennsylvania statehouse. In early April, roughly 4 million people attended more than 1,300 rallies across the U.S., demanding their leaders fight harder against Trump. The Fighting Oligarchy Tour, headlined by Senator Bernie Sanders and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, has drawn hundreds of thousands of people across red states. The grassroots is sending a clear message to sitting Democrats: Do better, or we’ll replace you with people who will.

Most in the party recognize this is a crisis moment. But every crisis is also an opportunity—a chance to rethink policies, reframe messaging, and recruit new leaders who can meet the moment. The last time Democrats were this deep in the wilderness was in 2005, when few outside the DNC had heard of Barack Obama. Republicans’ own search for answers in the wake of Mitt Romney’s 2012 defeat gave rise to Trump. When you hit rock bottom, anything is possible—and every transformative political figure of the modern age has emerged from a moment like this one.

It’s a sunny Tuesday in early spring, and Jake Auchincloss is sitting on a bench outside the Rayburn House Office Building. Auchincloss, a 37-year old third-term Congressman from Massachusetts, seems nervous, almost jittery, as he explains why he thinks everybody is getting the Democrats’ problems wrong. “I hear a lot: ‘Get a leader, let’s rally behind somebody.’ And I strongly disagree with that,” Auchincloss told me. “The forest of ambition is large. There’s no shortage of presidential timber. I’m worried about the ideas.” This is what keeps Auchincloss up at night: “It’s that we are bereft of big ideas.”

Auchincloss has a few. He wants to offer free one-on-one tutoring to kids who are behind in school because of COVID-19, subsidize community-health clinics, and hold social media corporations accountable for what he calls the “attention fracking” of America’s youth. But a decade of fighting MAGA, he says, has “depleted some intellectual dynamism” from his party. “In 2028, we’d better be ready to have dynamic candidates on the stage offering whole new ideas,” he warns, “or we’ll lose again.”

In our conversations, Democrats often made that argument. It’s not enough to say what we’re against, they’d say, we have to say what we’re for. But when I asked these same party insiders what that should be, most regurgitated ideas Democrats have run on for decades. Protect Social Security and Medicare! Protect abortion rights! Protect labor! OK, I’d say. What about new ideas? They mentioned their own pet projects: a bill blocking a supermarket merger; a bill addressing specific veterans’ issues; a bill ensuring the right to fix your own car. Somehow, I had a hard time imagining “permitting reform!” as a rallying cry capable of mobilizing millions of low-information voters.

“I’ve heard some folks say, ‘It’s not our policies, we just have to communicate better,’” says Representative Angie Craig, who is running for an open Senate seat in Minnesota. “It actually is our policies that swing-state voters aren’t with us on. For those colleagues who were calling to defund the police: our voters are not with you on that.”

Most Democrats now acknowledge that the progressive movement encouraged a kind of purity politics that hampered the party’s ability to win majorities. “We swung the pendulum too far to the left,” says Representative Ritchie Torres, who represents a Bronx district where Trump made inroads with working-class people of color, as he did in cities around the country. “We have become more responsive to interest groups than to people on the ground.”

Many Democratic officials believe the party moved too far left on social issues in particular. “There are some sports where trans girls shouldn’t be playing against biological girls,” says one lawmaker, adding that most of his fellow Democrats agree but are “afraid of the blowback that comes from a very small community.” Even abortion is up for a rethink. Some Democrats want a retreat from the enthusiastic embrace of abortion rights, and a return to talking about abortion as “safe, legal, and rare,” as Bill Clinton put it. “Refusing to say that even in the third trimester there’s no limits on it, it’s not where the average American is,” says another Democratic lawmaker. “The really embarrassing truth is Donald Trump is closer to the median voting on abortion than Democrats were.” Yet the fact these lawmakers would only share these thoughts without their names attached shows how much Democrats still fear antagonizing their liberal base.

Others insisted that the problem is one of emphasis. When Democrats spent so much time talking about other things—Student debt! LGBTQ rights! Police reform! Climate change!—voters decided they’d taken their eye off the ball. “You’ve got to be principally seen worrying about jobs and people’s pay and health care—economic issues,” says Representative Chris Deluzio, who represents a working-class district in western Pennsylvania. “And I think folks see too many Democrats as not caring principally about the economy.”

This theory might make more sense if Harris had run a 2024 campaign that was all about trans kids, abortion, and gun safety. Harris didn’t run that campaign. She offered tax credits to boost small businesses, proposals to lower the cost of groceries and childcare, and the most comprehensive affordable-housing plan ever put forth by a presidential candidate. And she lost. “Kamala Harris was talking about it,” says Representative Greg Casar of Texas, the chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus. “But nobody was hearing it.”

Senator Ruben Gallego met me outside the Senate gym, still slightly damp. Gallego, who was raised by an immigrant single mother and served in the Marine Corps, was a rare bright spot for his party last year. He outperformed Harris by 8 points in Arizona, handily won Latino men, and was one of only two new Democrats to win Senate battleground races. As we walked through the Capitol, Gallego, 45, describes his very simple message: “I’m here to bring you more security: economic security, and your personal family security.” It meant talking constantly about the cost of living, and taking a more hard-line stance on immigration than most of his Democratic peers.

When we arrived at his hideaway—Gallego was so new to the Senate that he had forgotten his key—the freshman Senator told me he didn’t necessarily think other Democrats needed to adopt his security message. He just wants them to speak like normal people. The party’s problem is bigger than bad messaging, he believes. The problem is caution. “Democrats in general are always fearful of messing up,” he said. “The Democratic mindset has been to run very tight, not open campaigns.”

I knew what he was talking about. Aides on the Biden and Harris campaigns were so cautious they’d often go off the record just to provide canned talking points. That approach, Gallego says, is self-defeating in the age of social media, where crafting the perfect sound bite can mean missing the moment altogether. “I told my team during the campaign: This is a vibe election,” says Gallego. “If we can match the policy with creating this vibe, this culture, that’s gonna break through across all modes and mediums.” His point was that the art of messaging has changed. It’s less about developing the perfect slogan, and more about authenticity, simplicity, virality. The more consult-ified something sounds, the less memorable it is.

Like Gallego, many moderate Democrats have particular critiques of the party’s economic message. “I think Democrats have made this mistake of saying, ‘I’m here to help the little guy.’ Nobody wants to be called the little guy,” says Representative Marie Gluesenkamp Perez, 36, who has won twice in a red district in Washington State. “The fatal mistake in politics is condescension.” She’s not the only Democrat who thinks the party erred by targeting their messaging to the most marginalized, rather than the vast, struggling middle class. Nearly 70% of voters in battleground districts think Democrats are “too focused on being politically correct,” according to brutal internal polling shared with top party leaders in March, while a majority think Democrats are not looking out for working people and are “more focused on helping other people than people like me.”

The focus on protecting the most vulnerable, in other words, has left many Americans feeling ignored. “I constantly get draft mailers in my office that say things like ‘Democrats are fighting so you could put food on the table.’ That is not aspirational,” says Mallory McMorrow, a Michigan state senator now running for U.S. Senate. To McMorrow, the Democratic message should be simple, universal, and optimistic: “Democrats fight for the American Dream,” she says.

Others believe the party has to emphasize a more populist pitch to counter Trump’s. “The Democratic Party needs to make as our central message that our goal is to break the unholy alliance between corporate greed and corrupt government,” Casar told me. “If somebody is more conservative than me on this social issue, or we may disagree on this foreign policy issue, at the end of the day people say: the Democratic Party puts me first and the billionaires last. And that’s what wins.”

One of the things that surprised me over the course of these conversations was the way a Sanders-style economic populism had gained traction with politicians not normally associated with the Sanders wing of the party. “Our economy is rigged because our government is rigged,” Chris Murphy told me. Democrats, he added, “have to wake up every morning thinking about how to unrig our government so that the corporations and the billionaires don’t always get what they want.” This was a man who stumped so hard for Hillary Clinton in 2016 that he was on a shortlist to be her VP. “I think it was a huge mistake for our party to view Bernie as some fringe threat to the party,” he says now. “Bernie’s message all along has been the crossover message, the message that appeals both to Democrats but also to a big element of Trump’s base.”

Five months ago, Kat Abughazaleh was an online journalist and researcher who made viral takedowns of far-right figures. But when she saw Democrats clapping politely during Trump’s second Inauguration, something snapped. “It was just so pathetic,” she told me, speaking on the phone from her home office in the Chicago suburbs. “I was like, ‘Well, maybe they’ll actually do something.’ And then they didn’t.”

Shortly afterwards, Abughazaleh, 26, announced a primary challenge to Representative Jan Schakowsky, an 80-year-old party stalwart who has served in Congress since the year Abughazaleh was born. Schakowsky wasn’t the worst member of Congress, Abughazaleh thought. They agreed on a lot of issues. But Abughazaleh thought Schakowsky wasn’t up to the moment. Her campaign announcement video asked a simple question: “What if we didn’t suck?” She raised more money in the campaign’s first week than Schakowsky did the entire first quarter. Within six weeks, Schakowsky announced she would not seek re-election.

Even if the Democrats generate new policy ideas and adopt a sharper pitch, they’ll still bump up against the core issue that tanked Biden, Harris, and much of the rest of the party last year: age. Many Democrats are finally realizing that too many of their leaders are too established, too out-of-touch, or simply too old to connect with voters.

Four House Democrats died in office over the past year. House Democratic Leader Hakeem Jeffries has acknowledged that Republicans could not have passed a budget resolution in April had their narrow majority not been widened by the deaths of two members of his own caucus. Of the 30 House Democrats who are 75 or older, more than half told Axios they planned to run for re–election next year.

Many Democrats are not eager only for generational change. They want change at the top of the party as well. Some see Jeffries and Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer as too deferential to established norms or too reluctant to use procedural powers to slow down Trump’s agenda. Both are underwater in public-opinion polls. Only 27% of Americans approve of congressional Democrats overall—the lowest number since CNN started asking in 2008. “I think the party is hyperfocused on message and forgetting about the messenger,” says Amanda Litman, the co-founder of Run for Something, which recruits new Democrats to run for office and supports them with training, mentorship, and campaign tools. “They’ve missed the way people consume information. You look for a person, not an institution.”A sclerotic party establishment has created a culture of waiting your turn. “All the people that are in formal leadership roles,” says Pat Ryan, “are ladder climbers, not leaders.”

At the DNC, Martin has locked horns with the party’s new vice chair, David Hogg, a survivor of the 2018 Parkland school shooting who rose to national prominence as a gun-safety activist. Hogg’s political organization, Leaders We Deserve, plans to invest $20 million to support young candidates challenging “asleep-at-the-wheel” Democrats in safe seats. Hogg tells me the party’s post-Biden “realignment” isn’t primarily about ideology. “It’s: Do you want to fight or do you want to roll over and die?” Martin has publicly rebuked Hogg, insisting the DNC maintain its long-standing position of neutrality. On May 12, the DNC’s credentials committee voted to void the elections of Hogg and another party official for procedural reasons they said predated the controversy, setting up the prospect of Hogg’s losing his position.

In the meantime, a new breed of Democrat is stepping up. They’re younger, more digitally fluent, more working class. They speak American without a D.C. accent. “People who haven’t been politicians for 30 years can go into a nonpolitical space and be a real person,” Amanda Litman told me as she walked to pick her children up from day care. These new candidates can talk persuasively about the costs of housing and childcare, issues that probably haven’t affected your life much if you’ve been in Congress since 1995. “It’s not the magic words,” says Litman. “It’s that many of these people can’t be credible messengers.”

Some new ones may emerge from the younger generation of Democrats who were elected in the 2018 wave after Trump’s first victory, and are now running statewide. Mallory McMorrow, 38, and Haley Stevens, 41, are vying for Michigan’s open Senate seat. Angie Craig, 53, is running for Senate in Minnesota. Abigail Spanberger, 45, is running for Governor of Virginia. Representative Mikie Sherrill, 53, is running for Governor of New Jersey. “The fight is generational,” Sherrill says. As soon as she arrived in Congress in 2019, she told me, she encountered an “entrenched” cohort of “collegial” lawmakers who -refused to update their strategic playbook because they kept waiting for politics to go back to the chummy inside game it had been pre-2016. “Do I think we need a new generation of leaders? Yes,” she told me. “But guess what: I think we’re about to get it.”

When Greg Casar arrived at the Tucson rally for Sanders’ and Ocasio–Cortez’s Fighting Oligarchy tour, the line of spectators stretched so long that Casar’s Uber driver thought he was going to a concert. Organizers had expected 2,000 people at a high school gymnasium; he said more than 10 times that many showed up. “People are even more opposed to what Donald Trump is doing than eight years ago,” Casar told me, fiddling with his AirPods as he sat outside a committee markup in late April. “But they want a new kind of leadership from the Democratic Party.”

As party leaders in Washington debate how to move forward, their grassroots base is sick of waiting for them to figure it out. Frustrated liberals have founded roughly 1,400 local Indivisible groups since the election, including more than 600 in GOP congressional districts. More than 46,000 young people have signed up to run for office through Run for Something since November. To those who participated in the “Resistance” movement of the first Trump term, the grassroots rage feels different this time. It’s not just targeted at Trump; it’s also focused on the feeble Democrats and spineless institutions who have failed to effectively resist him.

Some Democratic officials have responded by copying Trump’s own playbook. They’re favoring nonpolitical podcasts over cable studios, burnishing their social-media game, showing up at football games and Coachella. They’re trying to worry less about who they’re offending and more about who they’re reaching. Group chats of -Democratic lawmakers are full of delicate negotiations on how best to respond to the Trump presidency. “We recognize that the most important thing we can do is make this guy unpopular,” says one lawmaker. They’re sharing talking points and legal strategies, while weighing various acts of defiance against the potential for distraction. Internal discussions, says this lawmaker, are laser-focused on “figuring out what’s tactically smarter.”

Most Democrats expect a public outcry against Trump’s policies will help them retake the House in 2026. Winning back the Senate will be tougher, with more Democrats on defense in battleground states. In the meantime, a shadow presidential primary is already taking shape, with hopefuls drawing different lessons from Trump’s win and its aftermath. California Governor Gavin Newsom has started a podcast, featuring Trump allies like Steve Bannon and Charlie Kirk as guests, and pivoted to the center in his day job, cracking down on homeless encampments and pushing to reduce health care benefits for undocumented immigrants. Barnstorming against oligarchy helped Ocasio-Cortez raise $9.6 million in the first quarter of the year, rekindling speculation about her viability as a candidate for higher office. Cory Booker’s marathon Senate speech protesting Elon Musks’s cuts to the federal government was liked more than 350 million times on TikTok. And Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker railed against “do-nothing Democrats” in a speech in New Hampshire. As Pritzker put it: “The reckoning is finally here.”

Democrats are coming around to a new mantra: winning the argument is less important than winning elections. If the path to victory means embracing economic populism, they’ll do it. If they have to make room for new faces, then sayonara, old friends. If they need to tack to the center on some social issues, so be it. If winning requires doing more podcasts, or embracing Instagram influencers, or campaigning on permitting reform, they’ll give it a try. Because now that Democrats have seen what a second Trump presidency looks like, they’re relearning the lesson they should have known all along: only winning is winning.

Read the full article here