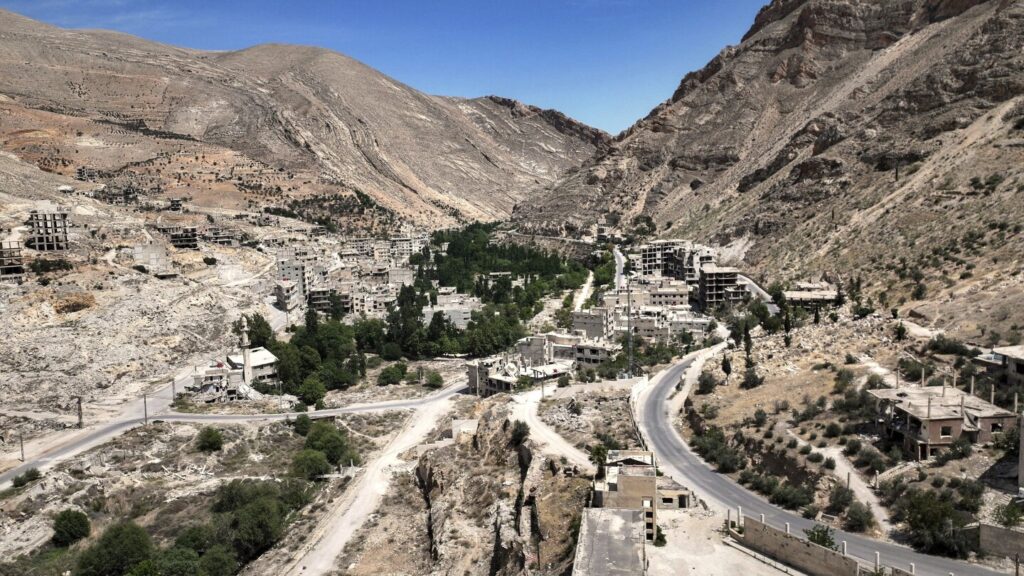

BARADA VALLEY, Syria (AP) — Inside a mountain above the Syrian capital, Hassan Bashi walked through tunnels that used to be filled with water from a spring famous for its pure waters.

The spring rises inside the ruins of a Roman temple in the Barada Valley and flows toward Damascus, which it has been supplying with drinking water for thousands of years. Normally, during the winter flood season, water fills all the tunnels and washes over much of the temple.

Now, there is only a trickle of water following the driest winter in decades.

Bashi, who is a guard but also knows how to operate the pumping and water filtration machines in the absence of the engineer in charge, displayed an old video on his cell phone of high waters inside the ruins.

“I have been working at the Ein al-Fijeh spring for 33 years and this is the first year it is that dry,” Bashi said.

The spring is the main source of water for 5 million people, supplying Damascus and its suburbs with 70% of their water.

As the city suffers its worst water shortages in years, many people now rely on buying water from private tanker trucks that fill from wells.

Government officials are warning that the situation could get worse in the summer and are urging residents to use water sparingly while showering, cleaning or washing dishes.

“The Ein al-Fijeh spring is working now at its lowest level,” said Ahmad Darwish, head of the Damascus City Water Supply Authority, adding that the current year witnessed the lowest rainfall since 1956.

The channels that have been there since the day of the Romans two millennia ago were improved in 1920 and then again in 1980, he said.

Darwish said the springwater water comes mainly from rainfall and melted snow off the mountains along the border with Lebanon, but because of this year’s below-average rainfall, “it has given us amounts that are much less than normal.”

There are 1.1 million homes that get water from the spring, and in order to get through the year, people will have to cut down their consumption, he said.

The spring also feeds the Barada River that cuts through the capital. It is mostly dry this year.

In Damascus’s eastern area of Abbasids, Bassam Jbara is feeling the shortage. His neighborhood only gets water for about 90 minutes a day, compared with previous years when water was always running when they turned on the taps.

Persistent electricity cuts are making the problem worse, he said, as they sometimes have water but no power to pump it to the tankers on the roof of the building. Jbara once had to buy five barrels of undrinkable water from a tanker truck that cost him and his neighbors $15, a large amount of money in a country where many people make less than $100 a month.

“From what we are seeing, we are heading toward difficult conditions regarding water,” he said, fearing that supplies will drop to once or twice a week over the summer. He is already economizing.

“The people of Damascus are used to having water every day and to drinking tap water coming from the Ein al-Fijeh spring, but unfortunately the spring is now weak,” Jbara said.

During Syria’s 14-year conflict, Ein al-Fijeh was subjected to shelling on several occasions, changing between forces of then- President Bashar Assad and insurgents over the years.

In early 2017, government forces captured the area from insurgents and held it until December when the five-decade Assad dynasty collapsed in a stunning offensive by fighters led by the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham group, or HTS, of current President Ahmad al-Sharaa.

Tarek Abdul-Wahed returned to his home near the spring in December nearly eight years after he was forced to leave with his family and is now working on rebuilding the restaurant he owned. It was blown up by Assad’s forces after he left the area.

Abdul-Wahed looked at the dry area that used to be filled with tourists and Syrians who would come in the summer to enjoy the cool weather.

“The Ein al-Fijeh spring is the only artery to Damascus,” Abdul-Wahed said as reconstruction work was ongoing in the restaurant that helped 15 families living nearby make a living in addition to the employees who came from other parts of Syria.

“Now it looks like a desert. There is no one,” he said. “We hope that the good old days return with people coming here.”

Read the full article here