On March 27, President Donald Trump issued an executive order titled, “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” which aims to root out the “corrosive ideology” that casts American history in a “negative” light. Critics have denounced this as an attempt to control ideas—part of a broader trend of unprecedented attacks against academic freedom and the independence of institutions of learning.

But the truth is that the push to align scholarship with government interests is not new. Throughout the 20th century, the relationship between colleges and the state was a messy one. American universities were vital to advancing the government’s power and global influence, especially through Cold War-related research and development. Nonetheless, they were also a threat to the government when scholarship challenged official narratives and agendas.

Today, Americans are witnessing a resurgence of such concerns. History shows that they may lead to censorship and curtail critical research—while also proving to be self-defeating. Many of the achievements that Americans most proudly celebrate were inspired by acknowledging the brutal realities of the past.

The Cold War exemplified the complicated relationship between universities and the federal government. As the conflict dawned in the late 1940s, the government quickly realized that universities could do more to help than simply provide scientific breakthroughs and defense materials: the humanities and social sciences could be just as valuable in fighting the Soviets.

At a time when the nation was engaged in ideological warfare, knowledge was power. Understanding the enemy—historically, politically, socially, psychologically, economically and culturally—was a matter of national security. And the government lacked the expertise necessary to understand foreign cultures and political systems. Officials understood that universities, by contrast, were well situated to provide this knowledge, so they enacted an array of programs to empower academics through grants and research institutes. The goal was to push scholarship toward topics that could inform domestic and foreign policy.

Read More: The True Story of Appomattox Exposes the Dangers of Letting Myths Replace History

As a result, over 20 years, the scale and scope of state influence on scholarly research grew dramatically. The government was instrumental in creating new academic fields, including area studies, and it shaped social science research for strategic purposes.

One example was the creation of the Russian Research Center, which was a collaboration between academics and the government. Based at Harvard and directed by Harvard faculty, its board was comprised of professors from various universities. It drew on expertise from different fields, including history, political science, economics, geography, law, anthropology, sociology, archaeology, and other disciplines.

Sigmund Diamond—a historian and sociologist who studied and briefly worked at Harvard during this period—chronicled the extent of the alliance. According to Diamond, although the center received a grant from the Carnegie Corporation, it reported directly to the State Department and other intelligence agencies.

Its mission was clear: to produce scholarly research and expert analysis useful to the government’s ideological warfare against the Soviet Union. This included studies on the attitudes of Russians toward their homeland in relation to the rest of the world—the sources of Russian patriotism, attitudes toward authority, and how Russians felt about the suppression of individual freedom. With this knowledge, the government could exploit discontent, foster instability, and leverage dissent against Soviet policies.

The center at Harvard was just one example; there were others at universities across the nation.

In the early 1960s, National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy delivered a lecture at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University. He emphasized the strong connections that “bind the world of power and the world of learning,” arguing that “there is gain for both the political world and the academy from an intensified process of engagement and of choosing sides and of engaging in the battle.” The government, in his view, would benefit greatly from historians whose work illuminated a “deeper sense of the realities of power and its use.”

But the government’s alliance with the academic community came with risks. If critical scholarship could dissect the enemy and boost American Cold War efforts, it could also be turned inward. Research disciplines that probed into the historical, political, social, and cultural vulnerabilities of other nations could also cast a critical eye on the U.S., raising sobering questions about American history and the nation’s unflattering record on civil rights, social unrest, imperialism, and more.

That made universities dangerous, and in the anti-communist hysteria of Cold War America, the government viewed them with suspicion. As molders of the nation’s youths, educators were under scrutiny lest they indoctrinate students with radical ideas. Government officials stoked this paranoia. “Countless times,” remarked Wisconsin Senator Joseph R. McCarthy—perhaps the era’s most prominent red baiter—in 1952, “I have heard parents throughout the country complain that their sons and daughters were sent to college as good Americans and returned four years later as wild-eyed radicals.”

Academics who offered critical assessments of the nation’s history and policies were suspected of communist sympathies; they caught the eye of the FBI and the government subjected them to surveillance and intimidation. In 1956, a survey of over 2,000 professors showed that 61% had been contacted by the FBI; 40% worried that students might misrepresent their politics; and about a quarter would not express their views for fear of the government.

The FBI targeted some historians in particular. The FBI considered them dangerous because of their ability to challenge patriotic myths and undermine the accepted narrative about the nation’s past. This was allegedly dangerous not only in the classroom, but also in the public square as it could raise questions about government policy. That risked stirring up public dissent and calls for reform.

Read More: A Historian’s Case for Protecting Even Offensive Speech on Campus

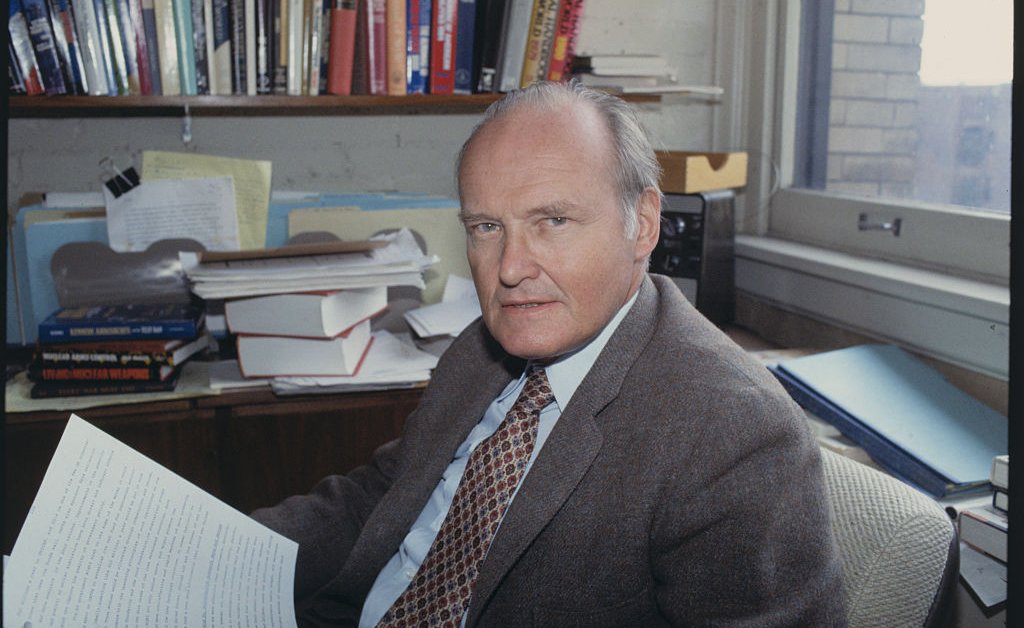

C. Vann Woodward, the Pulitzer and Bancroft Prize-winning Yale historian, was one scholar who landed under government surveillance for his critical views of America’s past. More than any other historian of the 20th century, Woodward’s writing exposed the horrific realities of racial segregation in America. He was also a staunch proponent of free speech and civil rights. Even Martin Luther King, Jr. drew inspiration from his scholarship. When Woodward criticized the House Un-American Activities Committee—which members of Congress used to engage in anti-communist witch-hunts—and signed a petition calling for its elimination, he provoked government scrutiny. The historian would later remark that his profession offered a corrective to the “complacent and nationalist reading of our past.”

But during the Cold War, the U.S. government had no patience for potentially subversive views about the nation’s past—even if they were accurate. It wanted scholars to offer penetrating insights into the history and politics of foreign regimes, but not at home. Patriotism became a litmus test, and scholars who applied their expertise to offer critical analyses of America’s revered narratives were suspected of harboring a dangerous un-American ideology.

Today, government anxieties about historical discourse have resurfaced. Trump’s executive order warns of a “distorted narrative driven by ideology rather than truth.” It condemns what his administration sees as an effort to “undermine the remarkable achievements” of the nation and “foster a sense of national shame.”

But the truth is that this directive risks undermining the potential for such “remarkable achievements” in the future. In many cases, including expanding civil (or legal) rights for African Americans and women, progress resulted from the work of scholars like Woodward and the way it empowered Americans to grapple with the less savory chapters in the country’s past. Americans acknowledged an un-sanitized version of U.S. history and worked to correct wrongs in order to ensure a brighter future.

The lessons from the Cold War’s record of state censorship of ideas are clear. Nuanced historical truth cannot thrive or die based on its political usefulness to the current administration. Suppressing the complexity of the nation’s past to curate a comforting national story will not lead to truth, sanity, or the sorts of achievements that Trump wants to celebrate. History matters, even if it does not align with the interests of those in power.

Trump’s attempts to control the narrative of American history is not merely a threat to academic freedom, but also to the nation’s ability to confront its past and shape better policies for the future.

Perhaps the President is right to worry about institutions of learning. Because knowledge, when un-policed, threatens the status quo. In a free society, that’s a virtue, not a threat.

Jeffrey Rosario is assistant professor at Loma Linda University in southern California. He is currently writing a book on religious dissent against U.S. imperialism at the turn of the 20th century.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

Read the full article here