Gwen Smith thinks lovingly of the three decades she spent living in Collier Heights, reflecting on a close-knit community filled with neighbors who knew one another’s names and were always eager to lend a helping hand when necessary.

But she can’t help but to remember the stench.

Smith recalls foul odors surrounding her community on multiple fronts: local landfills, a polluted creek, a now-defunct incinerator on James Jackson Parkway, a massive wastewater treatment center, the nearby Fulton County Airport.

“There were often just horrible smells. … The air quality was just not good,” said Smith, who founded the environmental justice nonprofit CHARRS (Community Health Aligning Revitalization, Resilience, and Sustainability) in 2015 to resolve health inequalities in Black and other marginalized local communities. “Sometimes you wouldn’t want to come outside.”

She didn’t realize it prior to entering the advocacy space, but those unpleasant funks were the byproducts of an array of probable community health hazards. And while the historic Black neighborhood in northwest Atlanta has made progress in addressing these dangers, the problems persist in and around the city — and have inspired Black environmentalists to take action.

While Atlanta is beloved for its lush tree canopy, local waterways, and ample hiking trails, the city faces environmental dangers due to the presence of industrial facilities and aging water line infrastructure, among other issues that disproportionately impact Black communities.

Changeseeking citizens are fighting back. In commemoration of Earth Day, local environmentalists spoke with Capital B Atlanta about the most pressing issues in their respective areas, how they’re working to address them, and why community involvement is crucial, in their own words.

These interviews were edited for length and clarity.

Jacqueline Echols, President, South River Watershed Alliance

Echols leads the South River Watershed Alliance, a nonprofit that is devoted to the protection and restoration of the South River, which has historically struggled with water pollution in stretches that run through Atlanta and DeKalb County — all of which impacts predominantly Black communities.

Jacqueline Echols says DeKalb County’s sanitary sewer system is responsible for much of the problems confronting the South River. (Eley Photo)

The biggest issue with the South River in DeKalb County is the sanitary sewer system. It’s old, it leaks a lot, and when it rains, stormwater gets into the sewer pipes, which aren’t big enough to carry that flow. That’s when you get sewer overflows into waterways, which violate the Clean Water Act.

Other than the DeKalb sanitary sewer system, Atlanta’s sewer system is one of the biggest sources of pollution into the South River.

No drinking water comes out of the South River. The biggest impact of sewage for the general public is recreation. When people kayak or canoe, they want to feel safe if they fall in. That’s why clean water is so important.

Sewage carries all kinds of contaminants — not just fecal matter, but also metals, because facilities that make different products around Atlanta all use the same sewer system. That affects fish and invertebrates, which are critical to a healthy waterway. If you don’t pay attention to the pollution you’re putting into a waterway, you won’t have any fish. You won’t have any invertebrates. Essentially, your stream is dead.

In this state, the only way to improve water quality is to recreate on a water body. If people aren’t on it, Georgia [Environmental Protection Division] doesn’t care. When I took over running South River Watershed Alliance in 2011, I said we need to get the community on the river. We need people who live near the river to care.

Most folks — even those who lived in south DeKalb County — didn’t know the South River existed. So that year, we launched a paddling and canoeing program called Beyond the Bridge. Black people, people who live in the community, folks who didn’t swim or kayak: all participated.

The South River Watershed Alliance launched a paddling and canoeing program called Beyond the Bridge to draw community attention to the South River. (Eley Photo)

Every three years, Georgia EPD has to reassess water quality due to recreation. I nominated the entire navigable length of South River for a change in designated use. It was designated for fishing, the state’s lowest water quality. We had eight years of data showing we took thousands of people down the river. In 2019, Georgia EPD designated 13 miles for recreational use, the state’s highest water quality.

Last August, the entire 40 miles of the river — from South DeKalb down to Jackson Lake — were approved for recreational use. If you can get that to happen, you can get environmental changes done in Georgia. That’s been the foundation of all of the improvements we’ve made to that river.

Now you have to get that enforced. We test water quality to identify sources of pollution when they occur, get them reported, and get them fixed. High E. coli counts means there’s a leaky sewer system, so we track upstream and find the source. We found several broken lines in Atlanta and DeKalb.

I would love to get community groups interested in testing water samples every couple of weeks from the stream in their neighborhoods. Regulators do better when the community is involved.

Renee Cail, President, Citizens for a Healthy and Safe Environment

For the past 12 years, Cail has headed Citizens for a Healthy and Safe Environment (CHASE), an organization that focuses on removing polluting industries that contaminate disadvantaged communities in and around Atlanta and educating residents about environmental issues and their health impacts.

Renee Cail said communities can find themselves caught between protecting the environment and attracting industry. (Kuwilileni Hauwanga/Capital B)

When Stonecrest became a city, it seemed like this was a dumping ground for developers. I understand that the revenue helps the economy. But in many instances, the industries that have hazardous chemicals are close to homes and schools. You don’t need to look in your backyard and see a manufacturing plant or trucks up and down the street every five minutes.

It’s a two-edged sword. You want to have good industries in your community, but then other corporations are allowed that should not be in close proximity to residents — especially if they have hazardous emissions.

Georgia has some of the highest pollution rates in the nation. People don’t realize every diesel truck that speeds past your house is detrimental to your health. In New Jersey, they have devices to keep emissions down. I don’t know the percentage, but not many trucks have them here.

Politicians who make laws don’t realize pollution doesn’t just stay in the Black or underserved communities. They don’t make laws that help keep people safe from these environmental issues or problems. I appreciate the ones that have stepped up, but it’s not a lot. And it’s not consistent.

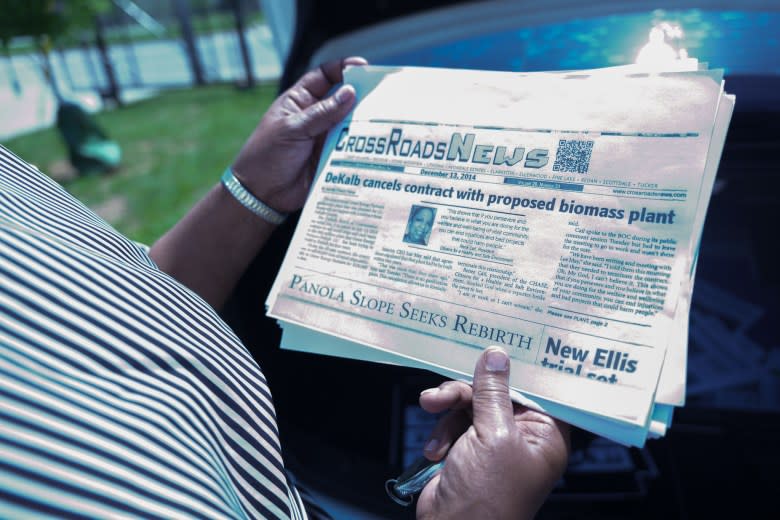

Cail calls the fight to stop a biomass plant from coming to Lithonia as a victory for the community. (Kuwilileni Hauwanga/Capital B)

Deborah Jackson, the former mayor of Lithonia, approached me in 2009 because there was a developer trying to bring a biomass plant to her city. Biomass plants generate electricity by burning anything that will burn. As a result, toxic chemicals get released into the air and particulate matter gets into the lungs, causing respiratory illnesses. So we mobilized the community. I met with people at the church I was attending. We did press conferences, canvassing, social media — whatever we could do to make people aware of what was happening and the associated dangers. It took us four years, but I feel proud of being able to push back the biomass plant. That was a victory.

Industries think Black people don’t have power and are not going to oppose these corporations. I’ve seen people join the movement because they are very shocked to find out what they’re inhaling and the impact that it has on illnesses they already have, like asthma.

The lack of information people have about what impacts their health is troubling. Be aware, research, educate yourself on pollutants, go to City Council meetings, ask questions. Community [members] are working to help keep each other safe. But there’s not a lot of support from the people who make laws and policies — especially when it comes to taking a strong stance against industries that are going to impact residents in an unhealthy way.

Gwen Smith, Founder, CHARRS

Through CHARRS, Smith works toward finding solutions to environmental justice issues that affect marginalized communities. Smith and other Black scientists teamed up to get a local air monitor set up in northwest Atlanta in 2023 to help fill in the information gap regarding the community’s air quality.

Gwen Smith worked with 2B Technology and other organizations to install air monitoring system in northwest Atlanta. (Eley Photo)

2B Technology reached out to CHARRS in 2022. They had a Small Business Innovation Research grant through the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences that required them to work with a community organization for air monitoring. They were testing their equipment and making it better.

They chose to work with five communities internationally; CHARRS and West Atlanta Watershed Alliance were the Atlanta organizations. They gave us seven handheld monitors and the stationary federal equivalency monitor. CHARRS said, “We want to make sure there are projects left in the community. We know you’re going to get what you want out of this, and then you’re going to leave. How can we work together so there’s some deposits left in the community?”

We don’t want just air monitoring, because just getting the data is not enough. CHARRS really wanted the community to understand the connection between what was happening in the environment — in the air — and their health. That would make the data more alive.

Smith says collecting data is just the first step: “CHARRS really wanted the community to understand the connection between what was happening in the environment — in the air — and their health.” (Eley Photo)

We started off by doing an environmental justice tour [in 2023] to show community members what is physically in their environment and how it’s impacting the natural environment and their health. We did a loop within this 3-mile perimeter of our project area, pointing out that there are two interstates and two highways running through the community, truck stops, rail yards, and facilities that are emitting pollutants into the air and have to report them. There are facilities in the area that could cost lives if they have an accident.

People on the tour were like, “We drive by this every day. We see it all the time, but it doesn’t register.” We need to make sure people understand what these things mean. That’s where it’ll make a difference. If you understand how something impacts you, then it could become a priority to you.

We are working with an epidemiologist to analyze the air monitoring data. My major concern is that we have to do more research. We need to be concerned about the amount of nitrogen dioxide in the air. It periodically spikes; we need to look at why that is. We’re hoping to do more monitoring to look at the connection between black carbon and nitrogen dioxide. Another concern is all of the construction on the Westside and the amount of particulate matter that kicks up into the air, gets into your lungs, and causes health hazards. Those are some major concerns.

The exciting news is that we are embarking on another year of monitoring; we’ve come to an agreement with 2B Technology to continue to use the monitor. I hope within the next year that we can train one or two students on maintaining this equipment. This could lead to a career — a whole new world of job opportunities. Having people from the community where this monitor is located become more knowledgeable about air quality, climate change, and how they can drive air quality improvement can lead to policy change.

The post Meet the Black Women Fighting for Clean Air and Water in Atlanta appeared first on Capital B News – Atlanta.

Read the full article here