Warm. Wistful. Tender. Empathetic. These are not words typically associated with Tina Fey, whose humor has a reputation for being brutal. But they all apply to The Four Seasons, a new Netflix dramedy series co-created by and starring Fey that follows three apparently settled middle-aged couples through a year of upheaval. Absent are the absurd characters, rapid-fire jokes, and dryly pessimistic social commentary with which Fey made her name on Saturday Night Live, and that have defined her career, from Mean Girls to 30 Rock. In their place is a moving depiction of marriage and friendship among Gen X empty nesters.

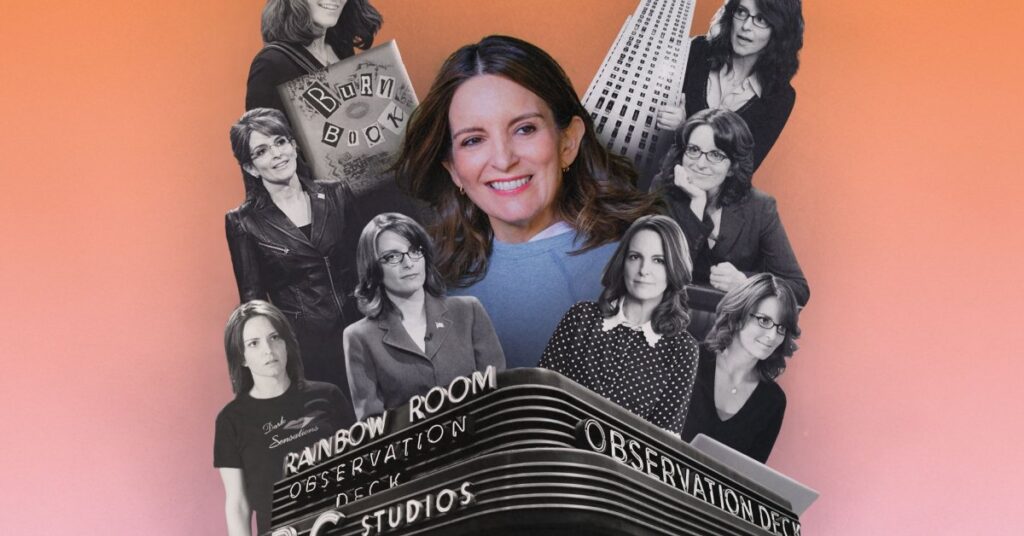

A partial explanation for the shift in tone is that The Four Seasons wasn’t entirely conceived by Fey and her collaborators, Lang Fisher (Never Have I Ever) and Tracey Wigfield (Great News). It’s based on writer-director-star Alan Alda’s 1981 film of the same name—an urbane box-office hit that has since been overshadowed by quintessentially ’80s rom-coms like When Harry Met Sally. As in Alda’s version, the title refers to four seasonal group vacations (two half-hour episodes apiece in the series), each set to the appropriate Vivaldi concerto. Alongside a cast stacked with fellow A-listers Steve Carell and Colman Domingo, Fey plays Kate, a responsible, high-strung pragmatist married to a passive, philosophical man, Jack (SNL alum Will Forte); Carol Burnett and Alda originated the roles.

Fey is well aware that this all represents a left turn for her. In a recent appearance on her old friend and sometimes comedy partner Amy Poehler’s podcast, Good Hang, she described it as “a very, very gentle program” whose reception she’s curious to observe. So compassionate is her approach, in fact, that it casts the nearly three decades’ worth of work that preceded it in a new light. Beneath the veneer of misanthropy and the din of controversy her perspective has often incited lies a more generous sensibility that was always present but is only now coming to the fore.

“Authenticity is dangerous and expensive,” Fey counseled Bowen Yang in a 2024 interview for Las Culturistas, the podcast that the current SNL star co-hosts. Yang had gotten too famous, she said, to keep broadcasting blunt opinions on people with whom he might someday have to work. “Are you having a problem with Saltburn?” Fey asked. “Keep it to yourself. Because what are you going to do when Emerald Fennell calls you about her next project, where you play Carey Mulligan’s co-worker in the bridal section of Harrods and then Act 3 takes a sexually violent turn and you have to pretend to be surprised by that turn?”

Both the substance of Fey’s playful excoriation—that when you’re a celebrity, anything you say can be used against you—and the fact that it went viral are telling. For most of her career, and certainly since her portrayal of the harried, unglamorous sketch-show head writer Liz Lemon in 30 Rock coincided with the rise of pop feminism in the late aughts, her every plot and utterance has been widely scrutinized. Tina Fey superfans may be legion, but she’s also absorbed more than her share of misogyny as well as criticism for her button-pushing approach to identity politics.

Plenty of the latter pushback has been not only justified, but necessary. Before the Black Lives Matter movement forced a reckoning in Hollywood, Fey made the poor decision to show white performers in blackface on 30 Rock. While the joke was always at the expense of an ignorant white character or a racist entertainment industry, context couldn’t outweigh the images’ hurtful impact. In 2020, she apologized and had those episodes pulled from streaming services.

Yet the hair-trigger sensitivities of audiences predisposed to judge Fey harshly have also fueled ridiculous backlashes. Following 2017’s white-supremacist rally in Charlottesville, the UVa alum caught flak for an SNL “Weekend Update” bit in which she jokingly urged viewers to drown their rage in cake instead of getting into fistfights with Nazis. No one watching in good faith could’ve mistaken her for excusing the marchers. (She even sneaked in unusually progressive opinions for broadcast TV: “It’s not our country. We stole it from the Native Americans. And when they have a peaceful protest, at Standing Rock, we shoot at them with rubber bullets. But we let you chinless turds march through the streets with semiautomatic weapons.”) Nor was it hard to see she was playing an exaggeratedly naive version of herself. Still, she was self-critical enough to judge the segment as a failure. “If I had a time machine,” she said on David Letterman’s Netflix show My Next Guest Needs No Introduction, “I would end the piece by saying… ‘Fight [the Nazis] in every way except the way that they want.’”

When Fey gets in trouble, whether for legitimate or specious reasons, it’s usually because her darkest humor is built atop a layer of cynicism about society—and Hollywood as a mirror of it—that isn’t always easy to unearth. Viewers got that her acclaimed SNL portrayal of an airheaded Sarah Palin reflected the then VP candidate’s pandering to a demographic that wanted women in politics to be “Caribou Barbie.” But they sometimes missed that the stars of 30 Rock’s show-within-a-show, Jenna Maroney and Tracy Jordan, embody certain awful stereotypes about white women and Black men not because Fey was saying they truly represented those groups but because showbiz rewards performers who reflect audiences’ prejudices.

It’s not hard to imagine why—at this point in her prolific career, but also at this toxic moment for the cultural conversation—Fey might want a break from satire. (She has long been rumored to be a top candidate to run SNL should her mentor Lorne Michaels ever retire, but her disinclination to keep wrestling the zeitgeist makes it seem doubtful she’d want the job.) Indeed, she appears to be making an effort to avoid stress in her professional life. Her current comedy tour with Poehler reportedly finds the duo bantering in pajamas. She spoke on Good Hang about making time, after years of overwork, to “just be a person in this world and maybe, like, watch a program.” In the same episode, Fey explained her approach to making The Four Seasons. “I worked hard to build it to be a really healthy set and really, like, humane hours,” she said. “I was also extremely purposeful about bringing together people who I believed were good people who would not make any trouble for me.”

The disproportionate share of criticism Fey attracts is, in a way, a testament to how effectively she’s caricatured herself over the years—as a schoolmarmish killjoy, a mousy prude, a blithely self-righteous white feminist—for an audience prone to conflating comedy with reality. She’s copped to having been a “caustic” judge of her peers as a teen, but the characters she usually inhabits, onscreen and as a public persona, are, to borrow words Fey frequently uses herself, “square” and “obedient.” A recent talking point has been her Enneagram personality test type: the Achiever.

Fey’s character in The Four Seasons is a more grounded, sympathetic version of this uptight woman. Kate can micromanage her friend group and her marriage, but when she errs toward officiousness, it’s because that’s her way of caring for people. “You’ve gotta always be the good guy,” she complains to Jack. “And that only leaves one other part.” The series is similarly generous with other characters. The revelation that Carell’s Nick plans to leave his wife Anne (Kerri Kenney-Silver) after a gathering for their 25th anniversary drives the plot, throwing off both the other two couples and the overall group dynamic. But Nick comes off as less of a jerk than he is in Alda’s movie and more of a man struggling with his mortality. While Anne fades into the background of the film post-split, Fey goes to great, sometimes a bit clumsy lengths to honor the perspective of the jilted wife.

Where was she hiding this humanism, after years of depicting characters at their vain, stupid, oblivious worst? In plain sight, actually. There is no better indicator of a writer’s worldview than how they end their stories. In that regard, Fey has always been sneakily optimistic. Mean Girls is often likened to the pitch-black high school satire Heathers, but Heathers concludes, after multiple murders, with its villain’s suicide, while Mean Girls leaves us with a reformed queen bee and a utopian teenage social order. Whereas Seinfeld, another deadpan NBC sitcom about self-absorbed New Yorkers, notoriously condemned its characters to prison, 30 Rock let Liz finally have it all: the career, the baby, the hot husband. Fey’s next big project, the Netflix comedy Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, wrung humor out of an abused, traumatized kidnapping victim’s adventures in a cruel city plagued by economic inequality. But—and here the clue is right there in the title—Kimmy’s tenacity won out.

The Four Seasons is probably not destined to become a classic like 30 Rock and Mean Girls; it offers neither the many madcap highs nor the occasional tone-deaf lows of Fey’s best work. Still, it’s a thoroughly enjoyable watch, one that reflects the wisdom and patience of age rather than the merciless genius of youth. Best of all, it reveals a hidden, humanizing dimension of the most fascinating character Tina Fey ever created: Tina Fey.

Read the full article here